Hey, low-enders! Discover the sonic and creative benefits of detuning your bottom string.

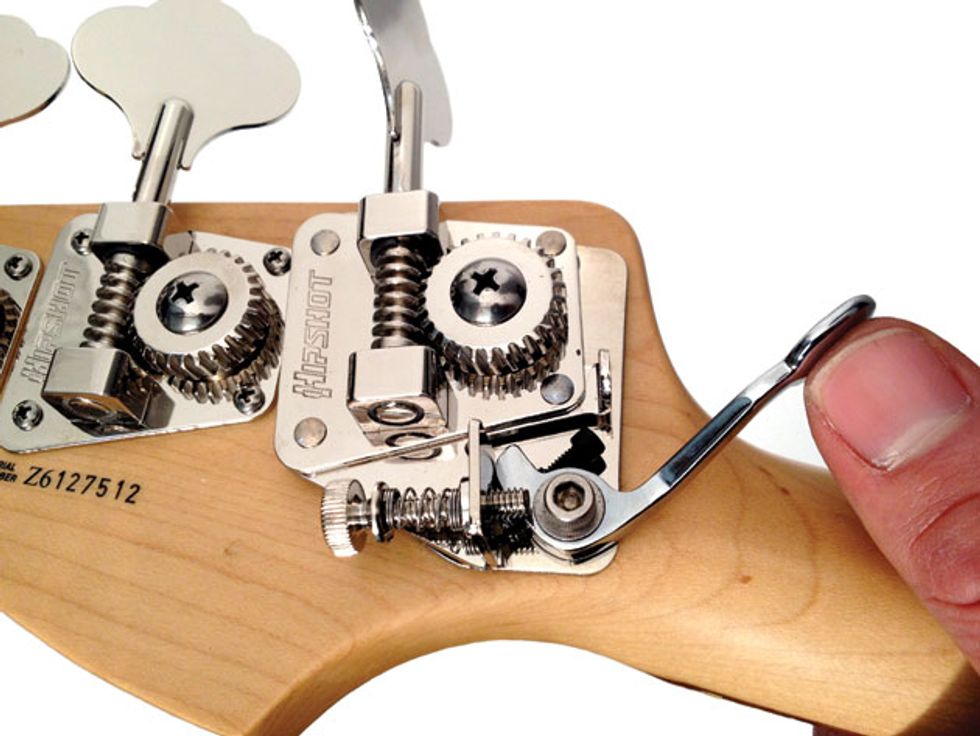

Fig. 1. Hipshot’s Double Stop Lever lets you access two pre-adjustable detuned pitches.

As we know, the electric bass has been tuned E–A–D–G since it made its debut in the early ’50s. This convention only began to change in the ’70s, after a few bassists managed to thrust their instrument into the spotlight. Today extended range, multi-scale basses use all sorts of tunings, yet most players stick with traditional perfect fourths tuning and rarely even think about changing it—even on their 5-stringers.

Extended-range basses didn’t appear overnight, and the initial attempts to add flexibility to low-end tuning were quite slow and tentative. D-tuners were the first little helpers for those in need of a quick low D, and they’re still relatively new. But dropped-D tuning itself has a much longer history, dating back to the Beatles, Neil Young, Pink Floyd, and even a guitar transcription of Bach’s Musette in D Major.

Of course this was accomplished by manual retuning, without the benefit of a quick flip of a lever. It was Hipshot’s Dave Borisoff who gave us that idea in 1984. He patented the device and after it caught Billy Sheehan’s attention at NAMM, Borisoff’s D-tuners (or Bass Xtenders, in Hipshot parlance) quickly became popular.

In the early years, Borisoff modified standard Schaller tuners to make his D-tuners, but once demand increased, he started his own production around 1985. Currently Hipshot produces a wide range of D-tuners for bass and guitar, but Borisoff didn’t stop there: He now also offers a Double Stop Lever upgrade (Fig. 1) that allows you to switch to two pre-adjustable pitches. Counting the original open E, you can choose one of three open notes for your 4th string.

As with many ideas from the adventurous ’80s, D-tuners have had their ups and downs over the years, but judging from the numerous requests I’ve had to install these devices, D-tuners show signs of being “up” again. Could this be a reaction to behemoth extended-range instruments? By heading for 9- or even 12-string “basses,” perhaps some players took it a bit too far and inadvertently kicked off a back-to-basics trend. A 4- or 5-string bass equipped with a dropped-tuning mechanism may provide the ideal compromise between simplicity and flexibility.

An intriguing thought: Since almost every metal band tunes down, it makes you wonder if country players shouldn’t tune up? If no one is tuning up, the future of bass must be to head even lower, yet there are only 30.9 Hz left under low B until the pitch hits DC.

Writing a column always involves some web browsing—and crossing paths with the ineluctable whiners. Reading their comments, you might wonder why anyone should bother trying anything new at all. The naysayers main concerns are (1) string breakage, (2) wearing out the nut, and (3) twisting the neck.

As for string-breakage: How often do we throw away a fairly good E string because of a dull-sounding or broken G string? Breaking an E-string does happen, but it’s far from being a real problem.

Every tuning process benefits from a slippery nut, and this is especially true when you switch between preset tunings. But this is why we have graphite nuts.

And then there is the change of tension when you drop the 4th string’s pitch. It’s easy to calculate using specific values (tension, frequency, scale length, and density) given by string manufacturers, but still, those tension differences hardly connect to the world of playing. So keeping the tension constant, the detuning would feel like the difference between going from a .100 E string to a .090 version. Assuming you only do this on one string, this small change would hardly require a new setup, much less threaten neck stability.

Fig. 2. Now upright bassists can get in on the dropped-tuning action. Photos courtesy of hipshotproducts.com

So if the cons don’t count, what benefits can a D-tuner provide? Correct—you’ll get a low D or even lower note, but there’s more. Ever noticed how quickly we get stuck in our habits? Changing your tuning can open new worlds of inspiration and pull you out of the monotonous loop of unvarying finger patterns. Instead of just buying new gear, why not push your creativity by relearning and mastering an altered fretboard?

Give it a try: Detune one or two strings and head out for your regular rehearsals or play a well-known song. If you’ve never done that, you’ll be surprised at the new brain activity! New tunings can bring out more musical creativity than a whole bunch of new stompboxes. And the “hand detuning” investment is a no-brainer because it lets you explore the benefits of a retuned your bottom string before opening your wallet.

Technically, there are more ways to detune than just using a rotating tuning key. Fig. 2 illustrates just one of these other methods. It also shows that upright players are not left out of the dropped-tuning game, but that’s a discussion for another time. The good news for gear heads is that manufacturers offer more than just one type of D-tuner, and we’ll dig deeper into those options next month.

Guest picker Mei Semones joins reader Jin J X and PGstaff in delving into the backgrounds behind their picking styles.

Question: What picking style have you devoted yourself to the most, and why does it work for you?

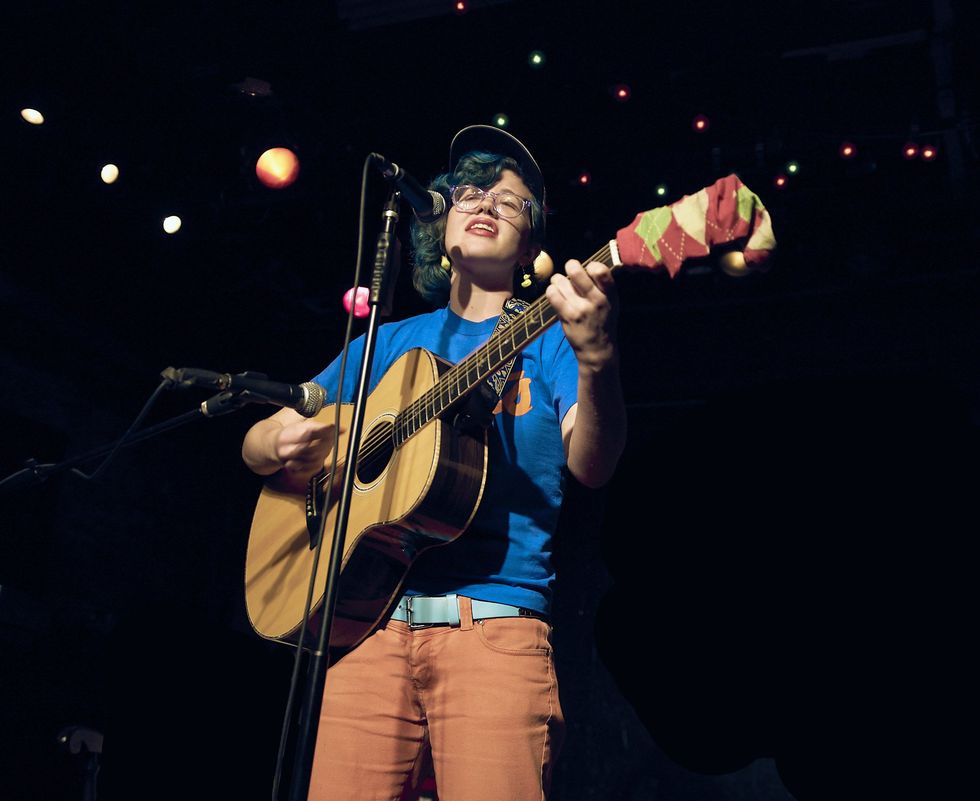

Guest Picker - Mei Semones

Mei’s latest album, Kabutomushi.

A: The picking style I’ve practiced the most is alternate picking, but the picking style I usually end up using is economy picking. Alternate feels like a dependable way to achieve evenness when practicing scales and arpeggios, but when really playing, it doesn’t make sense to articulate every note in that way, and obviously it’s not always the fastest.

Obsession: My current music-related obsession is my guitar, my PRS McCarty 594 Hollowbody II. I think it will always be an obsession for me. It’s so comfortable and light, has a lovely, warm, dynamic tone, and helps me play faster and cleaner. This guitar feels like my best friend and soulmate.

Reader of the Month - Jin J X

Photo by Ryan Fannin

A: For decades, the Eric Johnson-style “hybrid picking” with a Jazz III for “pianistic” voicings. Great for electric, though not so much acoustic. I’ve been recently learning to use a flatpick, à la Brian Sutton, by driving the pick “into” the string at an angle—which makes me think of Pat Metheny and George Benson, without irony.

Obsession: I’m still focused on understanding the concepts of jazz, neo-classical, and beyond, though I’m also becoming obsessed with George Van Eps’ 7-string playing, flatpicking, hip-hop beats, the Hybrid Guitars Universal 6 guitar, and the secret life of the banjo.

Editorial Director - Ted Drozdowski

A: Decades ago, under the sway of Mississippi blues artists R.L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough, and Jessie Mae Hemphill, I switched from plectrum to fingerstyle, developing my own non-traditional approach. It’s technically wrong, but watching R.L., in particular, freestyle, I learned there is no such thing as wrong if it works.

Obsession: Busting out of my songwriting patterns. With my band Coyote Motel, and earlier groups, I’ve always encouraged my talented bandmates to play what they want in context, but brought in complete, mapped-out songs. Now, I’m bringing in sketches and we’re jamming and hammering out the arrangements and melodies together. It takes more time, but feels rewarding and fun, and is opening new territory for me.

Managing Editor - Kate Koenig

A: I have always been drawn to fingerpicking on acoustic guitar, starting with classical music and prog-rock pieces (“Mood for a Day” by Steve Howe), and moving on to ’70s baroque-folk styles, basic Travis picking, and songs like “Back to the Old House” by the Smiths. I love the intricacy of those styles, and the challenge of learning to play different rhythms across different fingers at the same time. This is definitely influenced by my classical training on piano, which came before guitar.

Obsession: Writing and producing my fifth and sixth albums. My fifth album, Creature Comforts, was recorded over the past couple months, and features a bunch of songs I wrote in 2022 that I had previously sworn to never record or release. Turns out, upon revisiting, they’re not half bad! While that one’s being wrapped, I’m trying to get music written for my sixth, for which I already have four songs done. And yes, this is a flex. 💪😎

Guitarist, songwriter and bandleader Grace Bowers will independently release her highly anticipated debut album, Wine On Venus, August 9.

The new album adds to a breakout year for Bowers, who was recently selected as a U.S. Global Music Ambassador as part of the U.S Department of State and YouTube’s Global Music Diplomacy Initiative, is nominated for Instrumentalist of the Year at the 2024 Americana Music Association Honors & Awards and will make her debut performance on the legendary Grand Ole Opry on her eighteenth birthday, July 30, 2024. Other performances this year include shows supporting Slash, The Red Clay Strays and Brothers Osborne as well as stops at Levitate Music & Arts Festival, Floyd Fest, Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion, Bourbon & Beyond, XPoNential Music Festival and Pilgrimage Music & Cultural Festival. See below for complete tour itinerary.

Grace Bowers & The Hodge Podge - Tell Me Why U Do That (Official Video)

Produced by John Osborne (Brothers Osborne), Wine On Venus captures the electric energy of Bowers’ live performances with The Hodge Podge. The record consists of nine soul-infused tracks including a new version of Sly and the Family Stone’s “Dance to the Music” as well as previously release single, “Tell Me Why U Do That,” of which Forbes praises, “an infectious, joyous party and a worthy introduction to Bowers.” Additionally, The Bluegrass Situation declares, “an exceptional breakout talent who seems primed for a long career to come,” while RIFF Magazine calls her “The next generation’s star of American rock, blues and funk guitar.”

Of the record, Bowers shares, “I’m so excited to share my first album with the world in August! It’s been a long time coming, and I’m proud of what was created with the incredible Hodge Podge and John Osborne producing. We recorded everything live, as it should be, for this sonic journey. I hope you love it as much as I do.”

Additionally, of the title track, she reflects, “My nana was 100 years old when she passed away last year. She would always tell me that when she died, she would be drinking wine on Venus. She was a little eccentric but thought that was just something so cool. When she passed, I wrote a song about it.”

In addition to Bowers (guitar), the record features Joshua Blaylock (keys), Brandon Combs (drums), Eric Fortaleza (bass), Esther Okai-Tetteh (vocals) and Prince Parker (guitar) as well as songwriting collaborations with respected artists such as Ben Chapman, Meg McRee, Maggie Rose and Lucie Silvas.

Originally from the Bay Area and now calling Nashville home, Bowers began garnering attention after sharing videos of herself playing guitar on social media during the pandemic. In the years since, she’s been featured on “CBS Mornings” in a piece focused on a new wave of young female guitarists, performed alongside Dolly Parton as part of her Pet Gala special on CBS, joined Lainey Wilson as part of CBS’ New Year’s Eve Live celebration, performed as part of the “Men’s Final Four Tip-Off Tailgate Presented by Nissan” and been sought after by everyone from Devon Allman to Tyler Childers and Susan Tedeshi to Kingfish. Of her 2023 Newport Folk Festival debut, Rolling Stone declared, “Her 20-minute performance gave the distinct sense that everyone lucky enough to have attended was witnessing a star in the making,” while The Tennessean calls her “a 17 year old Blues guitar prodigy,” with a, “heart as big as her talent is vast.”

Most recently this summer, Bowers performed alongside Billy Idol at the Fired Up For Summer benefit concert and raised $30,000 for MusiCares and Voices for a Safer Tennesseewith her 2nd Annual “Grace Bowers & Friends: An Evening Supporting Love, Life & Music” benefit show. With the release of Wine On Venus (distributed by The Orchard), Bowers will further establish herself as one of music’s most intriguing new artists.

For more information, please visit gracebowers.com.

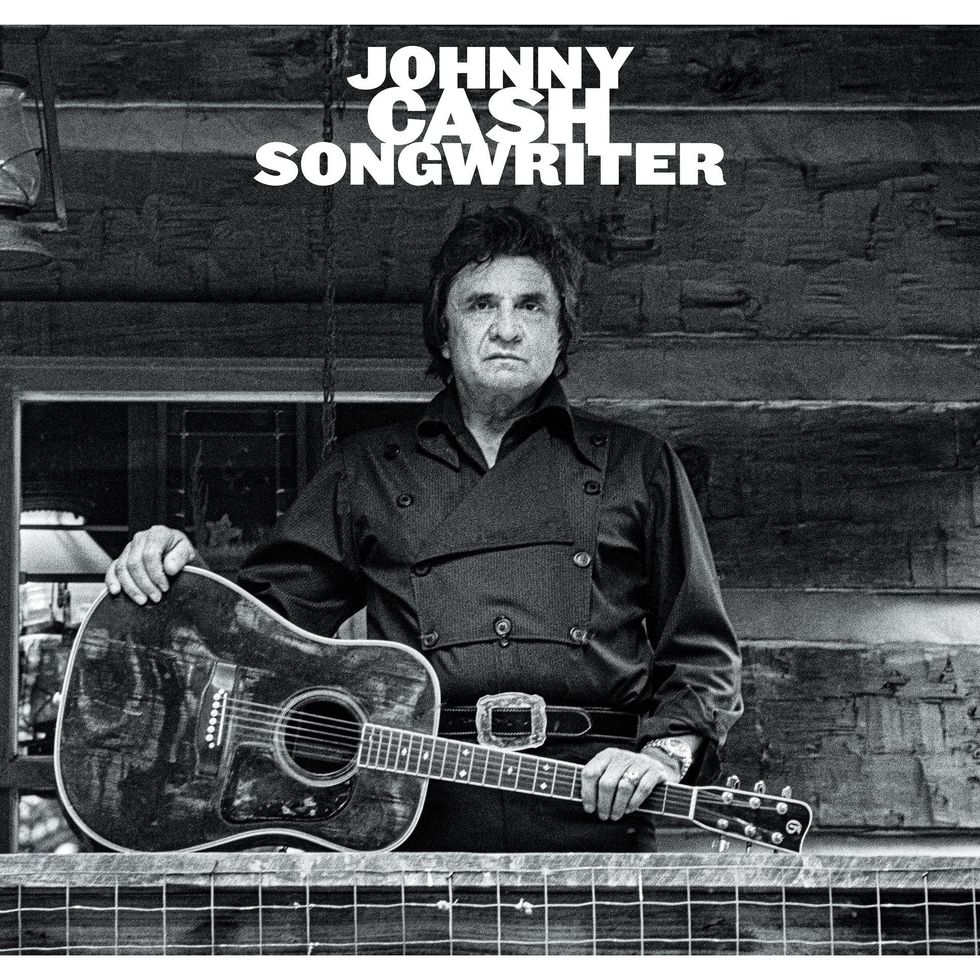

Johnny Cash on the front porch of the Cash Cabin in Hendersonville, Tennessee.

Cash initially shelved the album in 1993, but now his son, John Carter Cash, has spearheaded a project to revamp and release the recordings, with the help of Marty Stuart, Dan Auerbach, Vince Gill, and other notables. Read on to get the details and see a gallery of vintage instruments and other artifacts from the Cash Cabin studio.

“The Man Comes Around” is a much-played song from the final album Johnny Cash recorded before his death in 2003, American IV: The Man Comes Around. Now, the Man in Black himself has come around again, as the voice and soul of a just-released album he initially cut in 1993, titled Songwriter.

For fans who know Cash only through his much-loved American Recordings series, this is a very different artist—healthy, vital, his signature baritone booming, his acoustic playing lively, percussive, and focused. This is the muscular Johnny Cash heard on his career-defining recordings, from his early Sun Records sides like “Cry! Cry! Cry!” and “Folsom Prison Blues” to “Ring of Fire” and “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” to later, less familiar hits like “The Baron” and “That Old Wheel.” In short, classic Cash—the performer who became an international icon and remains one 21 years after his death.

In addition to theSongwriter album, it’s also worth noting that there is a new documentary, June, that puts June Carter Cash’s life and under-sung cultural legacy in perspective. Johnny wasn’t the only giant in this family. Just the biggest one.

“I think it’s important to support my father’s legacy in the world in which we live,” says John Carter Cash, who, in addition to his own work as an artist, is the primary caretaker of his family’s estimable body of work.

I recently visited the Cash Cabin—a log cabin recording studio on the Cash family property in Hendersonville, Tennessee, that was originally built as a sanctuary where Johnny wrote songs and poetry—with PG’s video team of Chris Kies and Perry Bean—to talk about Songwriter with John Carter Cash, the son of Johnny and June Carter Cash. [Go to premierguitar.com for the full video.] In this shrine of American music, Johnny Cash recorded most of the American Recordings series, and many others, from Loretta Lynn to Jamey Johnson, have tracked here. It’s also where John Carter Cash and co-producer David “Fergie” Ferguson took apart the original Songwriter sessions and put them back together, stronger, with musical contributions by Marty Stuart, Dan Auerbach, Vince Gill, a blue ribbon rhythm team of the late bassist Dave Roe and drummer Pete Abbott, backing vocalists Ana Christina Cash and Harry Stinson, percussionist Sam Bacco, guitarists Russ Pahl, Kerry Marx, and Wesley Orbison, keyboardist Mike Rojas, and John Carter himself. Johnny’s vocals and acoustic rhythm guitar, and guest vocals by Waylon Jennings on two songs, are all that was saved from the 1993 sessions, cut at LSI studios in Nashville.

In addition to getting the lowdown on Songwriter from John Carter Cash, he showed us some of the iconic guitars—including original Johnny Cash lead guitarist Luther Perkins’ 1953 Fender Esquire and a Martin that was favored by the Man himself—that dwell at the busy private studio. [Go to the video at premierguitar.com for an eyeful.]

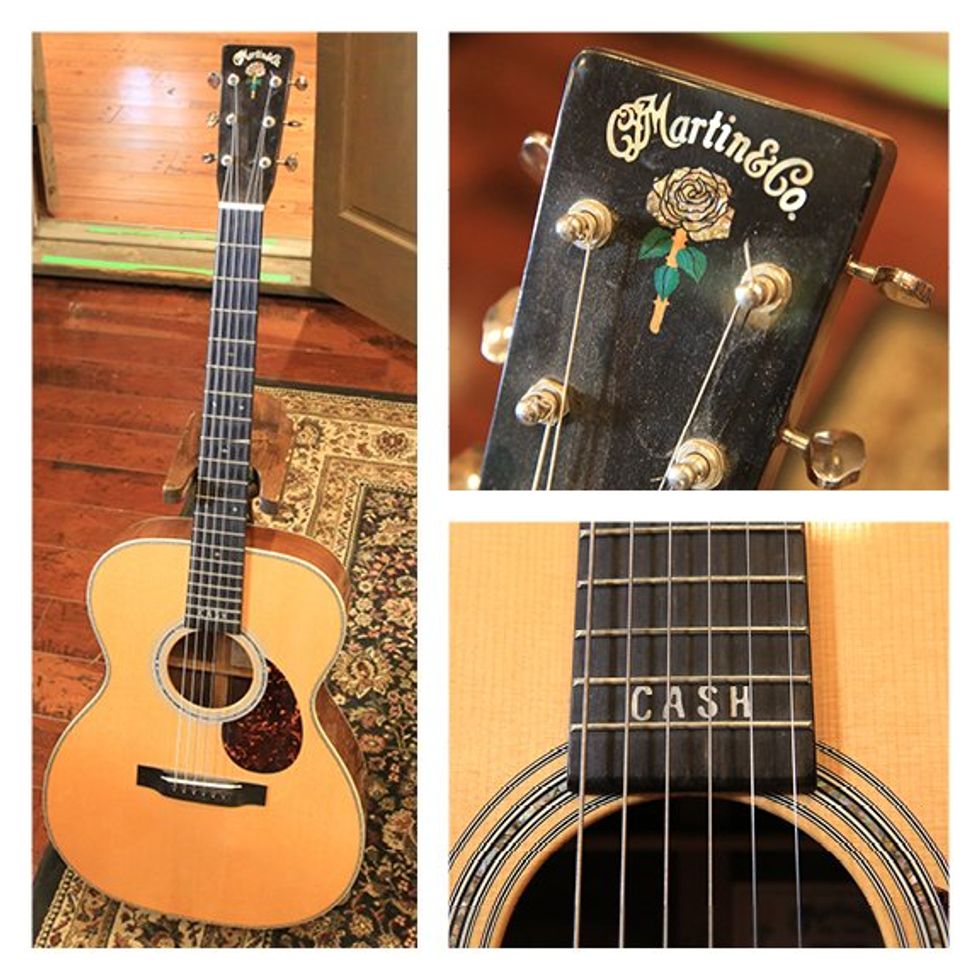

Only 44 of these Rosanne Cash signature model OM-28s were made by Martin. John Carter Cash says it’s his favorite guitar to play, and he and house engineer Trey Call attest that it’s probably the most frequently chosen instrument by guests recording in the studio.

Photos by Perry Bean

Only Johnny Cash’s original vocal and guitar tracks, and Waylon Jennings’ performances, were kept from the 1993 sessions. Marty Stuart, Vince Gill, Dave Roe, Dan Auerbach, and others contributed new tracks.

Speaking about Songwriter, John explains, “In some ways, these recordings fell through the cracks. I was in some of the sessions and can hear my guitar on some of the original recordings.” Dave Roe was also on those initial sessions, but he’d just started to play upright bass and didn’t have the finesse he lends to the revamped album.

The idea with Songwriter, John Carter relates, wasn’t to do anything more with the music than make it stronger. His dad was initially unhappy with the overall playing on the LCI recordings. “We didn’t add elements to make it about the ‘now’ or more ‘Americana’ or whatever,” he says.

The amp room at the Cash Cabin studio has some small but potent combo treasures.

Photos by Perry Bean

Nonetheless, Songwriter does take the Cash legacy to some new places, including the realm of psychedelia. Although the song “Drive On,” about a trucker who survived the Vietnam war with internal and exterior scars, was written for the 1993 sessions, it debuted in 1994 as part of the American Recordings album. The Songwriter treatment is radically different, from the panned amp, beating with tremolo, that opens the song to the concluding lysergic odyssey of 6-string provided by John Carter and Roy Orbison’s son, Wesley. It might well appeal to Johnny, who was a musical maverick—insisting that then-controversial figures like Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger, as well as a just-emerging Joni Mitchell and Linda Ronstadt, appear on the ABC network’s The Johnny Cash Show, which aired from 1969 through 1971.

This is June Carter Cash’s piano—an antique Steinway upright that still earns its keep as one of the studio’s active instruments. Nothing in the Cabin is a museum piece.

Photos by Perry Bean

John Carter, who is a singer-songwriter and producer, and is currently at work on his own fourth solo album, notes that the sonically spacious Songwriter opener “Hello Out There” resonates with him most, emotionally, as its lyrics balance the possible end of humanity with a message of hope. But every song on the album brims with empathy and kindness in strong measure. “Like a Soldier,” which blends Johnny’s patented guitar thrum with an introspective story about his battles with addiction, and “She Sang Sweet Baby James,” about a struggling single mother singing the James Taylor song to comfort her infant, are two more examples. And the guitars are always prominent, whether they’re Russ Pahl’s steel providing ambient textures or Marty Stuart’s hard-charging country licks, which breathe fire into the album.

A stained-glass portrait of Mother Maybelle Carter with her autoharp. Mother Maybelle invented a style of guitar playing, where melody was executed on the bass strings and rhythm on the high strings, that influenced Chet Atkins, Merle Travis, and a host of other famed pickers.

Photos by Perry Bean

For Stuart, who toured with Johnny Cash for six years and played on many of the Man in Black’s recordings, the experience of working on the retooled Songwriter, as well as his time with the senior Cash, was “mystical—everything about him was mystical. Even after I left his band, anytime the chief called, I was available. To the day he passed away, he was the boss. So when John Carter called and said he needed guitar on some of his dad’s tracks, I went over there. It’s so natural to hear that voice in the headphones. What I always loved about playing against him is that his voice is like an oak tree. You can put anything you want next to it, and it still stands out.”

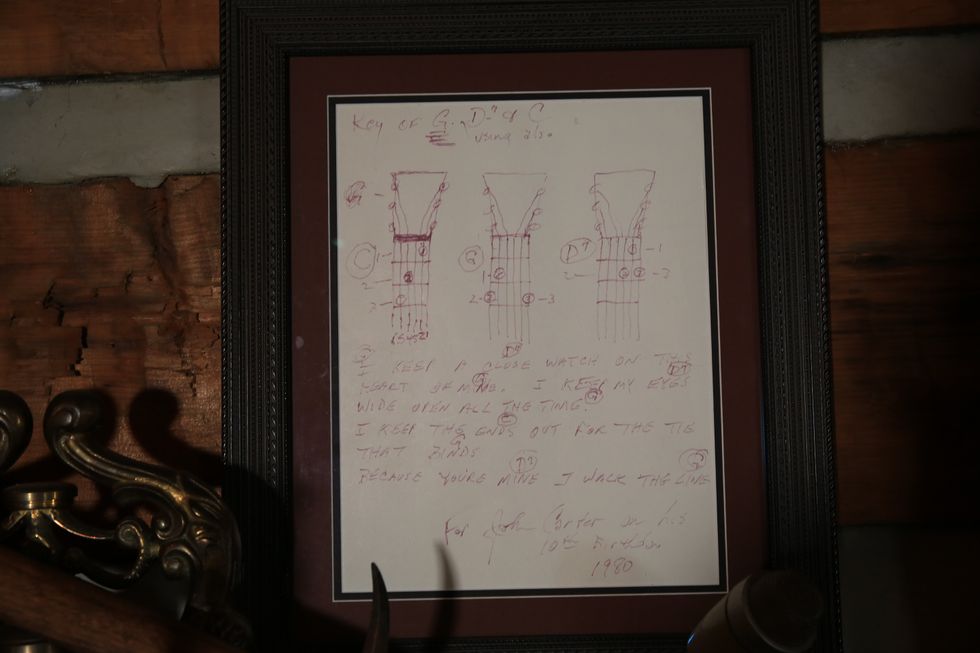

From father to son: On his 10th birthday, Johnny Cash drew John Carter Cash this chord diagram for “I Walk the Line.”

Photos by Perry Bean

The exterior of the Cash Cabin—one of the sacred places of American music and still a busy working studio.

Photos by Perry Bean

This 1953 Fender Esquire belonged to Luther Perkins, who was a member of Cash’s first recording bands and played on all of the Man in Black’s foundational recordings for Sun Records—likely with this guitar.

Photos by Perry Bean

Stuart’s instruments of choice for Songwriter were a ’50s Telecaster owned by Clarence White that bears the first B-bender, a 1939 Martin D-45 that Cash used on his ’60s/early ’70s TV show and gifted to Stuart, and a silver-panel Fender Deluxe, in addition to John Carter’s ’59 Les Paul, another of Johnny’s old Martins, and a baritone that resides at the Cabin. And Stuart’s focus was getting back to the template of Cash’s original Tennesse Two and Tennessee Three bands, and the guitar style created by Luther Perkins, Stuart’s first guitar hero. “They had their own language, and it’s a foundational sound inside of me,” he says. “With Johnny’s voice and the thumb of his right hand on the guitar as a guide, that architecture was all there. I heard the album the other day for the first time, and I thought, ‘Man, John Carter and David Ferguson worked their hearts out to honor the real sound.’”

John Carter Cash bought this 1959 Gibson Les Paul at Gruhn’s in Nashville. It has a neck that is atypically slim for its vintage and appears as part of the psychedelic guitar interplay on the Songwriter song “Drive On.”

Photos by Perry Bean

John Carter Cash remembers this Martin 40 H from his childhood as the guitar Johnny kept around the house to play on a whim or when he was chasing a song idea. The year is unknown, but as a guitar that Johnny Cash played, it is priceless.

Photos by Perry Bean

Here’s the headstock of the Stromberg that Mother Maybelle Carter used on the road while touring with Johnny Cash and her daughters. Her main guitar, dating back to the first recordings of country music, which she made as part of the Carter Family, was a Gibson L-5, but she judged this instrument hardier for travel.

Photos by Perry Bean

Fishing was a favorite pastime of the Cash family. This is June Carter Cash’s fishing reel and tackle box—one of the many personal and historic items in the cabin.

Photos by Perry Bean

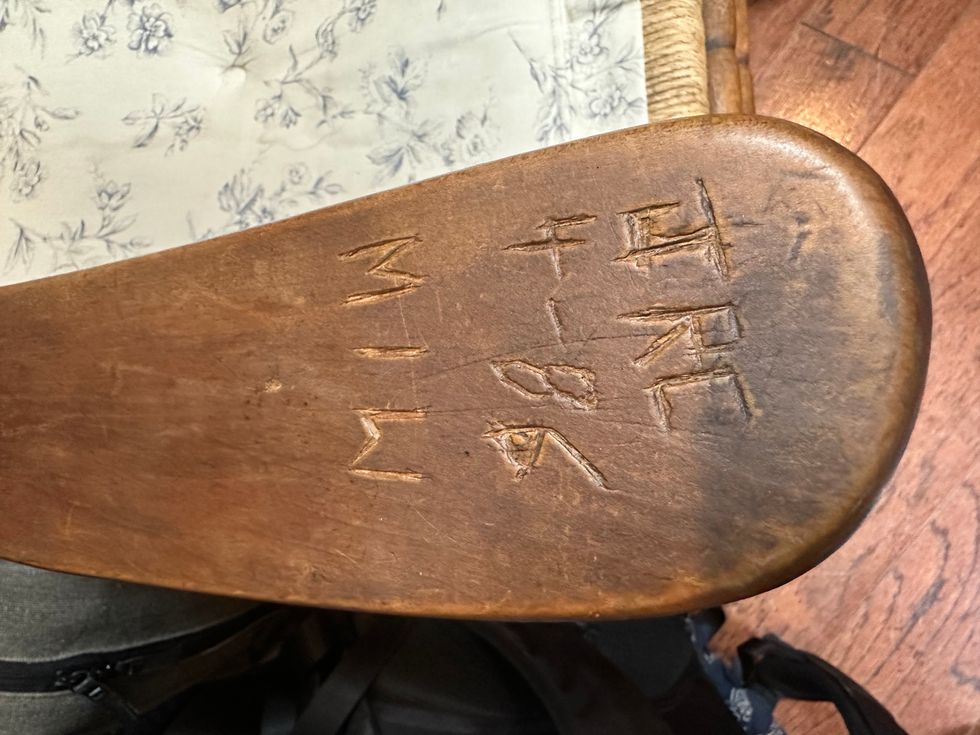

When Johnny Cash completed his novel about the apostle Paul, titled Man in White, he commemorated the occasion by scratching his initials and the day into the arm of the studio’s rocking chair—his favorite place to sit.

“In so many ways,” John Carter allows, “my father is always with me. People everywhere still love my father’s music. For instance, a 15-year-old kid wrote saying that without the strength through hardship my father expressed in his songs, he would not be alive. So, I think it’s important to support my father’s legacy in the world in which we live.

“My father made a distinction between the business of Johnny Cash and himself,” John Carter notes. “It’s almost like I’ve studied Johnny Cash my whole life, and so I can tie the two together somehow and still go through the healing process of losing a father while embracing him and his work on a level that spreads his music’s joy and brilliance to the world. I believe that his goal for his music and his life was to share with other people out there who connect on a level of the heart.” And that echoes, boldly, throughoutSongwriter.The new destination on Reverb will feature an always-changing collection of new and like-new music gear from top brands for at least 20% off retail prices.

“Outlet music gear is a fantastic value for music makers. Often, it’s brand new overstock or clearance music gear that retailers or brands are simply looking to clear out. Other times, it’s gear that’s been opened, used for a demo, or simply doesn’t have its original box, but is otherwise in like-new condition,” said Jim Tuerk, Reverb’s Director of Business Development. “With the launch of the Reverb Outlet, we’re making it easy to access your favorite brands for less.”

The Reverb Outlet will feature high-quality discounted music gear from Reverb’s community of authorized sellers, ranging from retailers like ProAudioStar and Alto Music to brands like Focusrite and Korg selling discounted items directly to music makers. All of the new and like-new music gear in The Reverb Outlet:

- Is at least 20% off retail prices—but often more

- Is sold by authorized retailers and brands

- Comes with free shipping, and

- Has a minimum 7-day return window.

“With economic pressures making it harder for music makers to invest in music gear, it’s more important than ever that the music-making community has access to affordable musical instruments. We launched the Reverb Outlet to make it easier for music makers to find the best deals on the instruments that will inspire them,” said Reverb CEO David Mandelbrot. “Now that players can shop discounted outlet music gear alongside our huge range of affordable used music gear, it’s easier than ever to find the perfect instrument for your budget.”

Visit the Reverb Outlet today and check back often, as new deals will be added regularly. Please note that as of now, this is available to those in the US only.

For more information, please visit reverb.com.